The case centers around the power of Parliament to amend the Constitution of India and the doctrine of basic structure.

Background Issue

In the late 1960s, the Government of Kerala introduced the Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963, which sought to implement agrarian reforms by imposing restrictions on landownership and distributing land to landless farmers. The petitioners, led by Swami Keshavananda Bharati, the head of the Edneer Mutt in Kerala, challenged the constitutionality of this law before the Supreme Court of India.

However, the case took a momentous turn when the scope of the challenge extended beyond the specific land reform law to question the broader issue of the power of the Indian Parliament to amend the Constitution.

The primary issue before the court was whether there were any limitations on the amending power of Parliament under Article 368 of the Indian Constitution. Article 368 lays down the procedure for amending the Constitution, and traditionally, it was believed that the amending power of Parliament was unlimited, provided it followed the prescribed procedure.

The petitioners argued that while Parliament had the authority to amend the Constitution, this power was not absolute and that there were certain “basic features” or “basic structure” of the Constitution that could not be altered through the amendment process. They contended that there were essential principles and values embedded in the Constitution that formed its basic structure and that any amendment that violated or abrogated these core principles would be unconstitutional.

The core issues before the court were –

- Whether there are any implied limitations on the amending power of Parliament, and if so, what are the limits?

- What constitutes the “basic structure” of the Constitution, and can it be identified and protected from amendments?

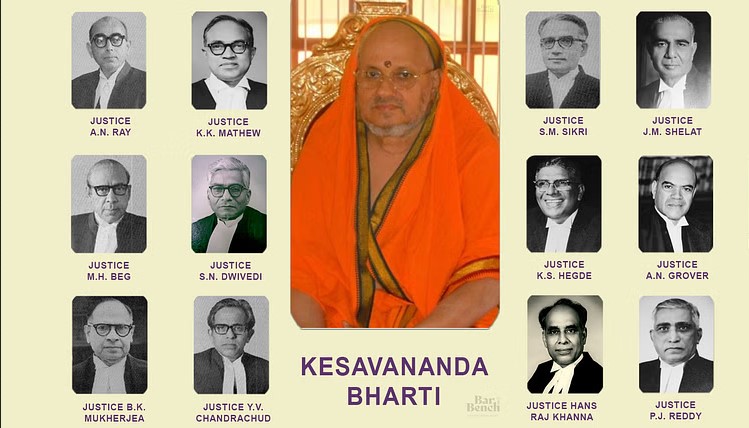

The case was argued extensively before a bench of 13 judges, which was one of the largest benches in the history of the Supreme Court of India.

The composition of the bench was as follows:

- S. M. Sikri – Chief Justice of India (CJI)

- J. M. Shelat – Judge

- A. N. Grover – Judge

- K. S. Hegde – Judge

- A. K. Mukherjea – Judge

- A. N. Ray – Judge

- D. G. Palekar – Judge

- H. R. Khanna – Judge

- K. K. Mathew – Judge

- M. H. Beg – Judge

- S. N. Dwivedi – Judge

- P. Jaganmohan Reddy – Judge

- V. R. Krishna Iyer – Judge

Judgment

On April 24, 1973, the Supreme Court delivered its landmark judgment in the Keshavananda Bharati case. The court ruled by a narrow majority of 7-6 that Parliament’s amending power was not unlimited. It held that while Parliament had the authority to amend the Constitution, it could not alter its “basic structure” or “essential features.”

The majority opinion was delivered by the 7-6 decision, with Chief Justice S. M. Sikri and Justices A. N. Grover, A. K. Mukherjea, D. G. Palekar, K. K. Mathew, M. H. Beg, and A. N. Ray ruling in favor of the petitioner, Swami Keshavananda Bharati. These judges held that Parliament’s amending power was subject to implied limitations, and it could not alter the “basic structure” or “essential features” of the Constitution.

On the other hand, the dissenting judges, Justices J. M. Shelat, K. S. Hegde, H. R. Khanna, S. N. Dwivedi, P. Jaganmohan Reddy, and V. R. Krishna Iyer, disagreed with the majority’s view and opined that Parliament’s amending power was absolute and unrestricted.

However, the court did not explicitly define the “basic structure” in its judgment, as that was left open for interpretation in future cases. Nonetheless, some of the judges mentioned certain core principles like the supremacy of the Constitution, federalism, separation of powers, and the democratic and secular character of the Indian state as part of the basic structure.

The judgment in Keshavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala marked a significant turning point in Indian constitutional law. It established the doctrine of basic structure, which has since been upheld and applied in subsequent cases to invalidate amendments that were found to violate the basic structure of the Constitution. The doctrine ensures that while the Constitution can be amended to adapt to changing times, its core values and principles remain sacrosanct and inviolable.Top of FormBottom of Form

The majority’s ruling in favor of Swami Keshavananda Bharati established the doctrine of “basic structure,” which has since become a fundamental principle in Indian constitutional law, limiting Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution in a manner that would violate its core principles and values.

The case involved one of the longest hearings in the history of the Supreme Court of India. The arguments were spread over a period of 68 days, from October 31, 1972, to March 23, 1973, and witnessed extensive and rigorous debates from eminent lawyers representing both sides.

The case was argued by some of the most renowned lawyers in India at the time. Nani Palkhivala, a distinguished jurist and constitutional expert, represented the petitioner, Swami Keshavananda Bharati. On the other hand, Attorney General Niren De and Advocate Fali S. Nariman appeared on behalf of the Union of India.

The doctrine of “basic structure” laid down in this case had a profound impact on subsequent cases related to constitutional amendments. It has been used by the Supreme Court in various cases to strike down amendments that were deemed to violate the basic structure of the Constitution.

Prior to the Keshavananda Bharati case, the Supreme Court, in its judgment in the case of Golaknath v. State of Punjab (1967), had held that Parliament’s amending power was unlimited and it could amend any part of the Constitution, including fundamental rights. However, the majority in Keshavananda Bharati overruled Golaknath and held that Parliament’s amending power was subject to implied limitations.

The judgment in Keshavananda Bharati was a result of delicate negotiations and consensus-building among the judges. Chief Justice S. M. Sikri carefully crafted the judgment to secure a majority, and some of the dissenting judges wrote separate opinions articulating their views on the scope of amending power.

The case is often regarded as a watershed moment in Indian democracy. The ruling upheld the principle of the supremacy of the Constitution and protected it from being amended in a way that could alter its basic structure. It reinforced the idea that the Constitution is the fundamental law of the land and serves as a bulwark against arbitrary and unfettered exercise of power.

The judgment in Keshavananda Bharati is seen as a testament to the independence and strength of the Indian judiciary. It demonstrated the court’s willingness to exercise judicial review and strike a balance between the executive and legislative powers to protect the fundamental principles of the Constitution.

The Keshavananda Bharati case remains a landmark in the history of Indian constitutional law and continues to influence the interpretation and understanding of the Indian Constitution. It symbolizes the judiciary’s role as a guardian of the Constitution and protector of the fundamental values and principles enshrined in it.

Keywords: Basic Structure, basic structure of the constitution, Kesavananda Bharati, Supreme Court of India Case Law, Judiciary, Parliament.